MEMORY-ESSAY.COM

#1

Balzac once terminated a long conversation about politics and the fate of the world by saying: “And now let us get back to serious matters”, meaning that he wanted to talk about his novels.1

CROCODILE PHILOSOPHY

Francis Fukuyama claimed in a Summer 1989 article in The National Interest that history was ending. He argued that the global crisis of communism pointed to “the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of government”.2 This claim is often mocked in retrospect for its broad sweep and inaccuracy, but Fukuyama included enough caveats in the article that his forecasting can’t be entirely dismissed despite its errors. For example, he speculated that communism might go on to be replaced in Russia not by liberalism but by a revived nationalism (Fukuyama actually wrote “Russian chauvinism”3), which is what duly happened.

But this way of looking at “The End of History?” is to treat it as an effort of objective, rather than aspirational, analysis.

At the time he published his article, Fukuyama worked at the State Department. The article was therefore institutionally linked to an official victory narrative. Fukuyama’s overconfident generalisations were to some degree ideological advocacy: the line between scholarship and propaganda was blurred, though this didn’t stop the arguments making a significant impact in both areas. “The End of History?” and the long book which followed three years later successfully shaped a wide debate. It wasn’t immodest that the title of The End of History and the Last Man dispensed with the original article’s question mark.

Fukuyama concluded “The End of History?” with some unexpectedly subjective remarks: “The end of history will be a very sad time. The struggle for recognition, the willingness to risk one’s life for a purely abstract goal, the worldwide ideological struggle that called forth daring, courage, imagination, and idealism, will be replaced by economic calculation, the endless solving of technical problems, environmental concerns, and the satisfaction of sophisticated consumer demands. In the post-historical period there will be neither art nor philosophy, just the perpetual caretaking of the museum of human history. I can feel in myself, and see in others around me, a powerful nostalgia for the time when history existed.”4 It is rather an odd passage: I notice a peculiar time-jumping, which placed the vaunted end of history first in the future (“will be a very sad time”), then in the wistfully remembered past (“the time when history existed”). The soon-to-be-regretfully-remembered mystique of self-sacrifice also puzzles me. Presumably the reference was to western, liberal cold warriors such as Fukuyama himself; however, given the mention of a threat to life, the mystique seems more relevant to the many communist or anti-imperialist rebels who died in the effort to establish a society managed scientifically to provide for everyone’s needs (along lines Fukuyama evidently didn’t approve). Much as time floated around in Fukuyama’s finale, so did the ideal of valour. It isn’t easy to work out what Fukuyama was really saying, or trying to say.

Perhaps the confusing conclusion reflected the burdens imposed on anyone in the dual role of bureaucrat and intellectual, anyone paid to combine state policy and academic analysis. Maybe what often goes along with mixed work of this sort is a daydream combining activism and emotional opennes (neither of which would normally be part of the job description). Yet if there was something romantic and even furtively rebellious in the whimsical ending of Fukuyama’s agenda-setting article, there may also have been something lost and burnt-out. If so, surely this emptier quality would have been closer than any adventurous daydream to the truth of the salaried philosopher’s stifled situation—and, what is more, closer also to the essential political truth of that sloganeering and bloody era of consolidation of elite power which the idea of the end of history, among others, conveniently but misleadingly promoted as dutiful technocracy.

“The end of history will be a very sad time”: a weird statement conveying to me only a distant or second-hand kind of sadness. Sadness may actually be quite difficult to define, but if it is anything more than a minor disturbance of mood, and more than nostalgia in the everyday meaning of the word, and if it is something different from despair, then sadness is a feeling deeply rooted in a person, in the past and in shared experience. To detach sadness from these painful foundations—to find it instead in the jumpy time and emotional inhibition of an ideologically charged, bureaucratic world-view—is to turn the profound feeling into a bullet-point. And perhaps this reductiveness was an inevitable companion of the ruthless political dishonesty which emerged in the neoliberal Nineties. Fukuyama’s shrunken “sad time” would in that case connect to the illogical and violent humanitarianism of the post-cold war era of crocodile tears: “I hope that no one who has seen what has happened in Kosovo to those refugees can doubt that NATO’s military action is justified. Bismarck it was who said that the Balkans were not worth the bones of one Pomeranian grenadier. But anyone who has seen the tear-stained faces of the hundreds of refugees streaming across the borders into Albania and Macedonia, heard their heart-rending tales of cruelty, or contemplated the unknown fate of those left behind can be in any doubt that Bismarck was wrong. This is, I believe, a just war, based not on any territorial ambitions but on good, decent values.”5 That credo was pronounced in 1999, the same year Thomas Harris published his novel Hannibal, in which a Grand Guignol character likes to mix the teardrops of a child, made to cry for the purpose, into his martini.

THEN AND NOW

Jacques Derrida, who was then at the height of his academic fame, responded quickly to The End of History and the Last Man in Specters of Marx, sparking a further vigorous sub-debate among professors about the Marxian legacy.6 I was coming to the end of my graduate studies when I read the English translation of Derrida’s book soon after it appeared in 1994. I read it with great interest, understood it as far as I could (which wasn’t far enough) and certainly I took it seriously. Coming back to the book thirty years later, its parochialism and self-importance annoy me, beginning with the preface. Specters of Marx and its companion volume of conference proceedings, the editors wrote, “explore the effects that the global crises engendered by the collapse of communism has had on avant-garde scholars, many of whom have lived through and often participated in these transitions themselves”.7 This barricades mythology was academic self-glorification in fine style.

Derrida was haughtily dissatisfied with Fukuyama and his audience. “Many young people today (of the type ‘readers–consumers of Fukuyama’ or of the type ‘Fukuyama’ himself) probably no longer sufficiently realize” that before Fukuyama popularised the subject of the end of history it had been explored at depth by the thinkers Derrida specialised in interpreting, who made up “the canon of the modern apocalypse” (as well as the main group of Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche and Heidegger, Derrida discussed a secondary canon of old favourites: Benjamin, Blanchot, Freud, Lévinas).8 True to the romance of the avant-garde professor, Derrida insisted on his unimpeachable Leftist pedigree as well as his philosophical mastery, referring to:

what we had known or what some of us for quite some time no longer hid from concerning totalitarian terror in all the Eastern countries, all the socio-economic disasters of Soviet bureaucracy, the Stalinism of the past and the neo-Stalinism in process (roughly speaking, from the Moscow trials to the repression in Hungary, to take only these minimal indices). Such was no doubt the element in which what is called deconstruction developed—and one can understand nothing of this period of deconstruction, notably in France, unless one takes this historical entanglement into account. Thus, for those with whom I shared this singular period, this double and unique experience (both philosophical and political), for us, I venture to say, the media parade of current discourse on the end of history and the last man looks most often like a tiresome anachronism.9

All these years later, I can’t take Derrida’s long-winded and boastful writing seriously any more. I can only read Specters of Marx with great impatience. It used to impress me, now I only value it for the indirect reason that it coined the term hauntology, which became central to Mark Fisher’s work.

Fisher took Derrida’s concept away from its original elitist circle. It is true that Fisher was himself an academically trained philosopher who referred extensively to the European canon, but he always combined formal philosophising with a focus on pop culture as well as a strand of often poignant autobiography. For Fisher, hauntology was an obscure subgenre of electronic music, created notably by the artist Burial, as well as a philosophical concept. There are many occasions in Fisher’s books—and, just as importantly, his blogposts and articles in music publications—when the reader can easily picture the writer-to-be in his formative phase as a clever Eighties student who saw the melancholic and unsatisfied songs of the time as vernacular, minor-chord analyses in miniature of an increasingly demoralised society. And those moments had none of the tiresome self-congratulation of professors insisting on their own radical credentials; instead they conveyed love of the material, enthusiasm to communicate to as wide an audience as possible, and above all a longing to move beyond the kind of lingering unhappiness which he heard in the songs and which he revealed he himself suffered from. He cited authorities respectfully, but Fisher never fully belonged to the academic world. His work was something else: a suburban, bedsit philosophy of resistance against an ideological tide which threatened to cut off all outsider hope—such as used to be the staple of pop music—for a fulfilling life in community.

He saw that the technocratic society Fukuyama promised would be peaceful and well-managed had quickly turned out to be more like a wasteland. What made the present so desolate, Fisher argued, was the ideology he called capitalist realism, which insisted that a world beyond capitalism could never come into being once the communist alternative had collapsed. There was a constant tension in Fisher’s engagement with this orthodoxy between the pain of the loss of hope for a better future, and a determination not to despair. It was surely this tension that made the experience of reading his work often so moving, but in his last books sometimes the courageous and unselfish fight for viable hope was eclipsed by the frightening idea of sadness which is no longer just an emotion, but has become a whole haunted–haunting environment of stolen futures and timeless losses: “The sadness ceases to be something we feel, and instead consists in our temporal predicament itself.”10

SILENCED

Mark Fisher and I were both involved with a magazine for several years. As time went on, we became friends. I stayed with him and his family at their home in Suffolk in the summer of 2012, but not long after this trip to the coast I left the magazine. Even though I knew that friendships made through work don’t usually last after the work has ended, I tried to stay in contact with Mark.

My first job after university was working as a publisher in a large organisation. During this employment I continued to do some academic research and wrote occasional journalism. This sideline was on rather a small scale; it wasn’t anything like Francis Fukuyama at the State Department producing “The End of History?” Still, I think I know a little about how an institution impacts a young worker’s identity. Corporate rules, often unwritten, make a powerful impression. I always had my own daydreams of escape but when I left the job after an entire decade, it came as a surprise how hard the separation was, how different the reality of exiting was compared with escape in theory.

This reminds me that when I met Mark—it would have been around the time he turned forty—he was in a precarious position. It was only later that he secured half-time lecturer posts at two different London universities. His newfound security was established just when I was myself going in the opposite direction, tearing myself away from the professional world again, though more irreversibly this time, which for better or worse I was able to do if only because, unlike Mark, I had no family obligations, and also because it wasn’t my first escape. I am not saying it was much easier the second time around.

A few months after leaving the first workplace, I met a former colleague on a bus, someone I had always got on well with. When I said hello, he responded with unmistakable coldness. He didn’t exactly blank me but he put up a barrier. Suddenly I saw another side of the institutional rules, and later I thought about the creepy, powerful pressure of certain kinds of silence and conversational clampdown. There can be so much coercion and rejection involved in politely dismissive dialogue, such quiet violence, and all because of the demands of some group loyalty.

I have searched my inbox and found the last two emails Mark and I exchanged, both from September 2015. The background was that I had proposed a joint writing project. Mark replied with interest, warned that he was busy, but suggested meeting at the end of the month; I wrote back with possible dates. That was the last I heard from him, and less than two years later he died. I remember that when it seemed likely after a few weeks that what turned out to be my final email to Mark wasn’t going to be answered, it didn’t occur to me to worry about him exactly. Instead I assumed that this was the last stage in the unavoidable fading away of a work friendship. But because I couldn’t be sure this was the explanation, I left a voicemail. Still no answer came.

During my visit to Suffolk, Mark and I walked by the sea. I remember I felt there was a barrier between us, though not like the one that was put up on the bus. I had the sensation again a couple of years later, while I was with someone else who would shortly afterwards take his own life. It was only after the second man’s death that I realised this was how I used to feel often when I was with my father, who didn’t commit suicide, not directly anyway, and now I would say it is the feeling someone can get in the presence of a sadness which has managed to become a horrible surrounding, a force field—“it is as if the sorrow comes from the outside”,11 Mark Fisher wrote, “a kind of invisible barrier constraining thought and action”12—until, in the saddest cases of all, the person left or lost on the other side of it can no longer be reached.

WHO KNOWS WHERE THE TIME GOES

Derrida’s project of deconstruction was anti-religious. There was a rejection of what he termed in Specters of Marx any “onto-theological or teleo-eschatological program or design”,13 where “program or design” were typically dismissive labels. In an alarmist paragraph later in the book, Fukuyama the Hegelian liberal was scorned for his so-called “neo-evangelism” and on the same page Derrida envisaged a future “Holy Alliance” between post-communist Russia and Roman Catholic “Old Europe”.14 This implausible hypothesis—or conspiracy theory—suggested that Derrida the illustrious “avant-garde scholar” was in this area conservatively dedicated to a secular, European status quo which was hostile in its bones to the thought and tradition of its vast eastern neighbour: not just the regime so easily and smugly denigrated as Stalinist or neo-Stalinist, but even Russia in the chaos of its re-emergence out of the ruins of the Soviet Union. For it was possible that this wounded Russia, if it survived, might reclaim its old and eschatological faith. In keeping with the underlying hostility, this French philosopher’s book about the downfall of communism cited no Soviet or Russian sources, not even dissident ones. (Fukuyama, by contrast, did cite such sources.) By defending the elitist, atheist supremacy of Franco-German philosophy, to the extent of excluding any native voices, Derrida was in his own way as much of a liberal cold warrior as the State Department philosopher he belittled.

Derrida claimed authority on the basis of his canon—Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche and Heidegger, to name the chief figures once more—in addition to his institutional seniority in several universities, and also by force of in-group terminology and rhetorical repertoire. While the style of Specters of Marx wasn’t outlandish for what was after all a specialist academic book (though no doubt one which its author hoped would break through to a wider audience, as Fukuyama’s had) the added complication is that Derrida’s waffling account of time and history being haunted and nonlinear was arguably much less original than it purported to be, especially if the religious thought he discounted is allowed back into the discussion. To illustrate the point, it is enough to recall a famous Christian view of time’s paradoxes which was expressed in very plain though poetic language—

Time present and time past

Are both perhaps present in time future

And time future contained in time past15

—and then to set that beside, first, a passage from Specters of Marx, and after it another from Russian religious (and anti-communist) philosophy, in order to gather that Derrida’s formulations were distinctive by virtue of their jargon rather than their content:

Before knowing whether one can differentiate between the specter of the past and the specter of the future, of the past present and the future present, one must perhaps ask oneself whether the spectrality effect does not consist in undoing this opposition, or even this dialectic, between actual, effective presence and its other.16

The Russian Social Revolution in all its grandeur and fullness will one day take its place in a far-off past. It will however continue to live in the present of that future. There will then also be new factors which we cannot foresee and those new elements without doubt will be ranged against the immediate past. But they too will be unable to annihilate the force of the past. The past and the future will mingle anew. Such is the mystery of time and history.17

And with that I have nothing further to say about Jacques Derrida.

ETHOPOEIA

The fear some felt in the Soviet Union after 1945 was that Nazism could revive like a savage vampire rather than some maudlin and theatrical spectre. The anxiety was expressed near the end of an interestingly wry documentary made by Mikhail Romm, Triumph over Violence (1965), for example. It began to be conceivable that the European memory of Nazi atrocities could fade, despite or perhaps because of the sheer scale of them, and that dormant hatreds could in responsible memory’s absence come back to life. Attempting to prevent such a forgetting, some Soviet artists worked to preserve first-hand accounts of what had happened in the territories which formed the post-war Eastern Bloc. One of these artists was Ales Adamovich, who travelled extensively in his native Belarus collecting testimonies from survivors of Nazi wartime massacres. (Adamovich’s writing later formed the basis of the harrowing 1985 fiction film Come and See, directed by Romm’s student Elem Klimov.) The interviews with survivors gathered in a book such as Out of the Fire needed to be published, Adamovich and his co-authors said, because “some people keep trying again and again to white wash this plague of the 20th century in the eyes of new generations, who themselves did not experience the horrors of the Second World War”.18

I won’t discuss the testimonies in Out of the Fire directly here. They are very sad and disturbing to read, and it isn’t possible to do them justice in this short essay. I will however quote one comment made by the authors, and italicised by them for emphasis, in order to acknowledge what is at stake in the record of the mass murder in Belarus and beyond: “No matter what we have heard and read about nazism, these people have seen it at a far closer range than we, have seen right at their side the bared teeth of the ‘superbeast’ at a moment when there was no longer anything to separate the nazi and his victim and the nazi’s whole nature, everything there was in him, was laid before his victim’s eyes.”19 In putting down this brief marker, I think it worth adding that academic work is now being produced in Britain which openly characterises the commitment in Russia to maintain this history as state propaganda. Probably Specters of Marx and The End of History among numerous other works contributed to the intellectual culture in which such an argument can seriously be made.20

A prosperous, technocratic, peaceful idyll was Fukuyama’s victorious—or burnt-out—daydream of life in the universal liberal society created by the end of history. But there was always another way to think about culmination, about ultimate things, in the nuclear epoch after 1945. People took stock of the industrialised slaughter of the concentration camps together with the immeasurable open-air massacres, and many of them concluded that something had changed forever in the world. Inevitably the problem of theodicy—of how evil can exist if there really is a God—became relevant to these reflections, and writers like Camus in The Rebel went back to Dostoevsky’s monumental presentation of the problem in The Brothers Karamazov.

To summarise briefly: Ivan Karamazov rejects God (though not His existence) during a conversation with his devout younger sibling Alyosha, who is an attendant of Father Zosima, an elder of the local monastery. Ivan’s humanitarian argument stems from what he calls the “unredeemed tears” of tortured and murdered children: “Is there a creature in the whole world who’s able, who has the right to forgive? I don’t want any such harmony; out of love for mankind, I don’t want it. I prefer to remain with sufferings unexpressed. It’s better if I remain with my unavenged suffering and my unappeasable indignation, even if I’m wrong.”21 This impassioned and often-quoted speech doesn’t stand on its own in the novel. A number of other statements and episodes make up a chorus, but what Ivan says is usually contrasted most of all with Father Zosima’s doctrine of all-encompassing Christian love which is described in the novel shortly after Ivan’s declaration to his brother.

Ever since The Brothers Karamazov’s publication, readers and critics have wrestled with this virtual dialogue between Ivan and Father Zosima, and in the Soviet Union it was naturally no scandal to side with Ivan, especially given that the Nazis had in living memory perpetrated acts which even the fictional Ivan, who admits he keeps a scrapbook of atrocity reports, might be said to have never imagined. Yet it is also noteworthy that Dostoevsky’s treatment of theodicy should have remained a reference point for at least some Soviet readers, given that this conservative and religious novelist, who had bitterly satirised the revolutionary movement of his time, was out of kilter with state ideology. Gorky, in his role as a leader of Soviet writers, in a 1934 address called Dostoevsky a genius but expressed revulsion at the content of his novels: “Dostoevsky has been called a seeker after truth. If he did seek, he found it in the brute and animal instincts of man, and he found it not to repudiate but to justify.”22

So perhaps it followed logically that Soviet readers should have felt free to pick and choose what they took from Dostoevsky, whose work anyway is profoundly ambiguous—specifically to favour Ivan’s stubborn humanitarianism over Father Zosima’s doctrine of forgiveness, and to do so on the basis that the world war had once and for all demonstrated the extent of the human capacity for evil, the further proof being that people could soon afterwards begin to ignore or downplay the truth of that demonstration. Thus another Soviet chronicler, working with a method similar to Adamovich, Svetlana Alexievich, paraphrased Ivan’s words and attributed the sentiments to Dostoevsky himself.23 The trouble is—if the novelist’s work of fiction is taken seriously as fiction—that the words are, all the same, still the character Ivan’s words and in The Brothers Karamazov, as Camus pointed out, Ivan is going mad.24

Listening to his brother, sweet Alyosha is bewildered and then horrified. His reaction to Ivan’s diatribe is theological and emotional not philosophical or humanitarian—“That’s rebellion”,25 he says as a rebuke—and Dostoevsky underlined the young Christian’s words by calling the whole chapter “Rebellion”.

Perhaps it is the case that, after the killing fields behind the eastern front, and after the death camps, Alyosha’s objection simply can’t any longer hold up against Ivan’s obdurate denial—perhaps the twentieth century created a whole Ivan Karamazov World. I am, however, not sure about that, and so I will have to return to the question in my own way another time. For now, I will end by quoting Out of the Fire again, at length.

Because Adamovich and his collaborators also took Ivan’s side, but instead of paraphrasing Dostoevsky and leaving it at that, they kept the issue open by preserving some words of Father Zosima intact, albeit under protest. They then added their own reworking of the elder’s doctrine, using the figure of speech which rhetoricians call Ethopoeia—that is, speaking on behalf of another, or in this case on behalf of all the survivors of the massacres who felt that there could be no end to their sorrow. And by doing both these things in tandem, the writers echoed Ivan’s objection while leaving in view the other side of the argument, meaning that the very form of the supplemented citation allowed for the possibility that in addition to all the horror and the grief, in addition to the proud and dignified labour of commemoration, there might still be new beginnings of a kind the writers themselves couldn’t for the time being imagine, and not only the forever sadness:

“…God raises Job up again and restores his wealth; many years pass by, and he has other children and loves them all. Good Lord, ‘How could he love those new children when the other ones were no more, when he had lost them? Remembering them, could he really be fully happy, as in the past, with the new children, no matter how dear the new ones were to him?’”

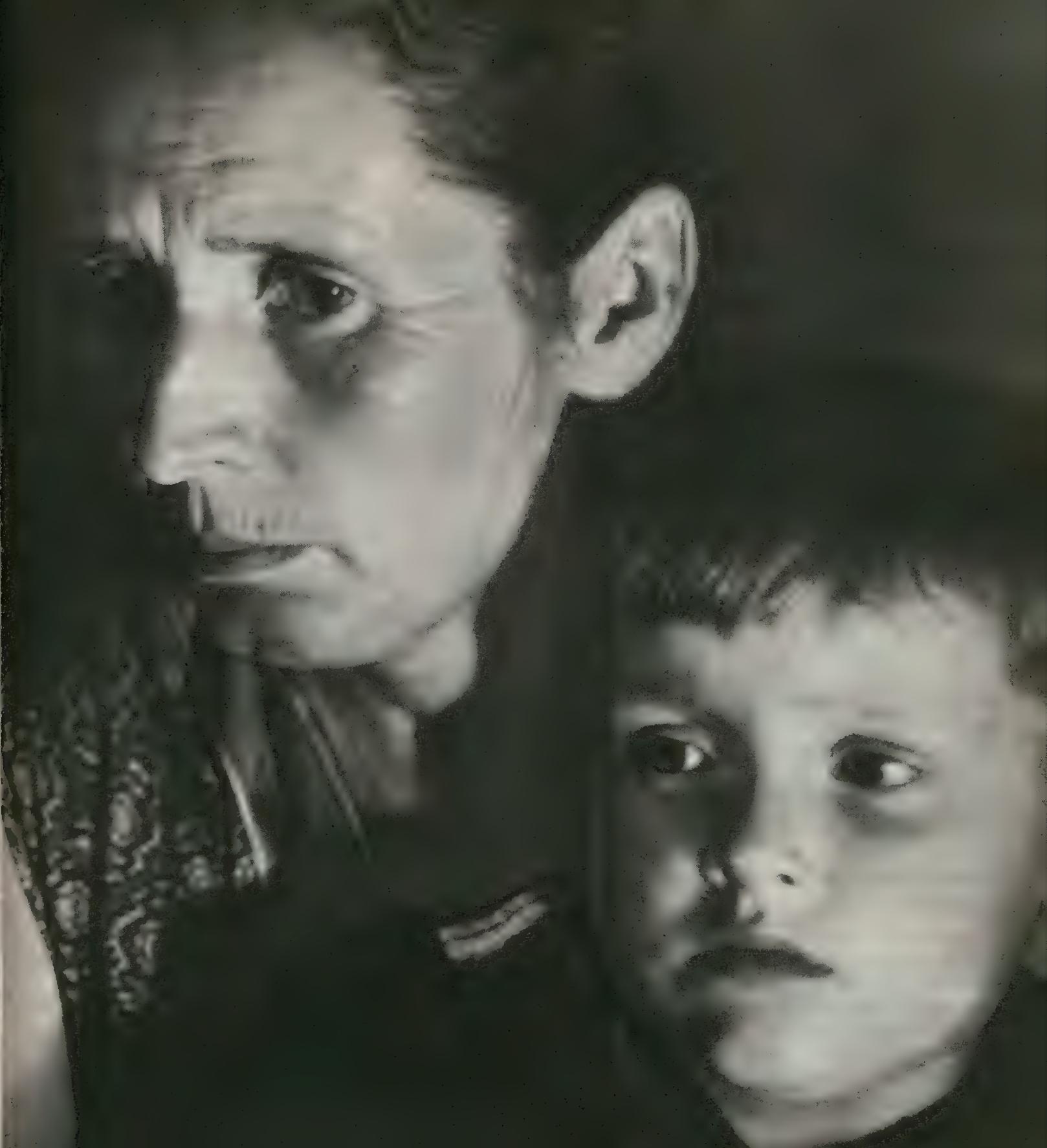

The nineteenth century was far from untroubled. But in this century the experience Dostoyevsky describes was the fate of millions of mothers and fathers. All this can be read in the eyes and faces, discerned in the voices of so many villagers.

The authors continued:

Yes, a people’s capacity to survive, its natural strength is most important. The people who are quoted in this book are not merely “bringing back” their own children. They are bringing life itself back to life.

Yes, these people have not lost their memories of the past. We sense this in their eyes and voices as they tell us about their present life and their “new” children.

Perhaps starets Zosima is right in a way when he expresses Dostoyevsky’s hope (and also doubt):

Recalling those dead and gone can one really be completely happy? “But one can, one can! Through the great mystery of human life, the old sorrow gradually turns into quiet, tender joy,”

This is a truth of life.

You read it in people’s eyes, in their faces. But you also read something else, something hidden deep within. Something expressed, even cried out as if in unbearable pain, by the Byelorussian novelist Kuzma Chorny, the bard of the village folk. He did not express it in the quiet voice of Zosima but in the outcry of Ivan Karamazov. This is quite natural in our 20th century with its scales… The fate of an entire people was involved. And the very real pain and suffering of people so alive in the memory, so dear to the heart…

“A priest was telling the congregation about how God tested Job’s faith. He sent all kinds of misfortunes on him… He knew it was God’s punishment but he didn’t stop praying to God and praising him, he didn’t cherish a grievance against God. God gratified him for this by returning everything he had… more children were born to him, just as many as had died before… For thousands of years people have been told this story and can it be that nobody ever realized that you can’t say such a thing to people because it is a grave lie… If I started another family and if I once more returned to life—had a new house, had my own bread to eat and again had a little son running out to greet me, I could get used to living in another house or riding another horse… But my dead child—it lived, it saw the world, it knew I was its father! There might be another child but it would not be the one who experienced the suffering and that suffering will remain forever because it was real and nobody can ever make it unreal.”

This we could sense in the most quiet voices, as if addressed to the whole world!…26

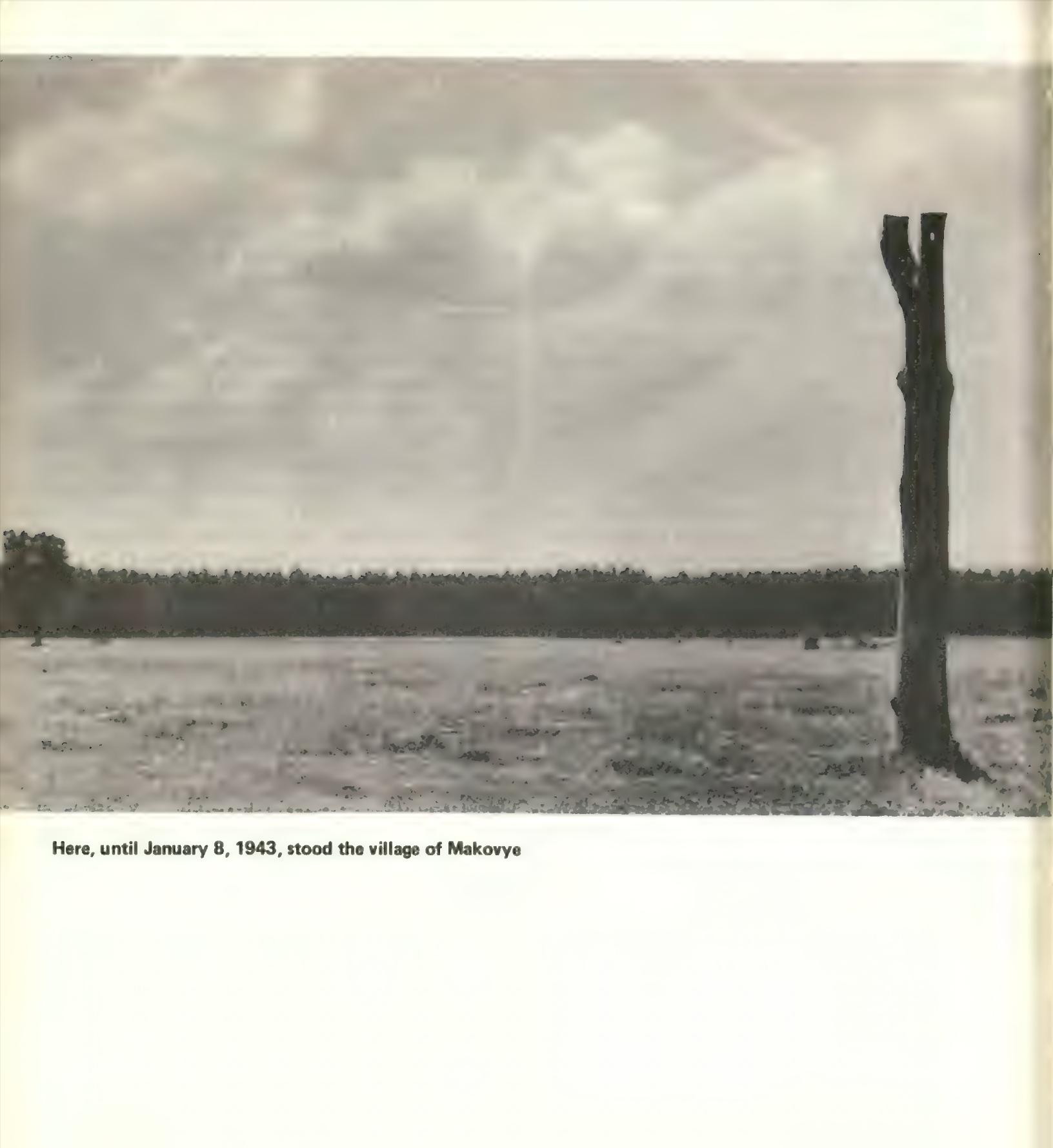

above: pages from Ales Adamovich, Yanka Bryl and Vladimir Kolesnik, Out of the Fire, trans. Angelia Graf and Nina Belenkaya (1977; Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1980).

NOTES

1. Albert Camus, The Rebel, trans. Anthony Bower (1951; Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1973), p. 226.

2. Francis Fukuyama, “The End of History?”, The National Interest, Summer 1989, 3–18: p. 4.

3. Ibid., p. 17.

4. Ibid., p. 18.

5. Tony Blair, speech delivered at Economic Club of Chicago, 22 April 1999. Transcribed from video of the event available on Youtube here.

6. See Jacques Derrida, Terry Eagleton, Fredric Jameson, Antonio Negri and others, Ghostly Demarcations: A Symposium on Jacques Derrida’s “Specters of Marx” , ed. Michael Sprinker (1999; London: Verso, 2008).

7. Jacques Derrida, Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning, and the New International, trans. Peggy Kamuf (1993; London: Routledge, 1994), p. xi.

8. Ibid., p. 14.

9. Ibid, p. 15.

10. Mark Fisher, Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures (Alresford, Hampshire: Zero Books, 2014), p. 181.

11. Fisher, Ghosts of My Life, p. 180.

12. Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (Ropley, Hampshire: Zero Books, 2009), p. 16.

13. Derrida, Specters of Marx, p. 75.

14. Ibid., p. 100.

15. “Burnt Norton” (1935), in The Complete Poems and Plays of T. S. Eliot (London: Faber and Faber, 1985), p. 171.

16. Derrida, Specters of Marx, pp. 39–40.

17. Nicolas [Nikolai] Berdyaev, Towards a New Epoch, trans. Oliver Fielding Clarke (1947; London: Geoffrey Bles, 1949), pp. 74–5.

18. Ales Adamovich, Yanka Bryl and Vladimir Kolesnik, Out of the Fire, trans. Angelia Graf and Nina Belenkaya (1977; Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1980), p. 6.

19. Ibid., p. 402.

20. In Memory Makers: The Politics of the Past in Putin’s Russia (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2023), Jade McGlynn refers negatively to “the way in which Russia has progressed along a path that passes through cultural obsession and arrives at the total securitization of the memory of 1939/41 to 1945 and other historical interpretations” (p. 17).

21. Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov, trans. Michael R. Katz (1880; New York: Liveright, 2024), pp. 290, 291. Italics in original.

22. Maxim Gorky, “Soviet Literature”, in Gorky, Karl Radek, Nikolai Bukharin, Andrey Zhadanov and others, Soviet Writers’ Congress 1934: The Debate on Socialist Realism and Modernism in the Soviet Union (1935; London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1977), p. 46. No translator is named.

23. Svetlana Alexievich, Last Witnesses: Unchildlike Stories, trans. Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky (1985; London: Penguin, 2019): “Dostoevsky once posed a question: can we justify our world, our happiness, and even eternal harmony, if in its name, to strengthen its foundation, at least one little tear of an innocent child will be spilled? And he himself answered: this tear will not justify any progress, any revolution. Any war. It will always outweigh them” (p. xi).

24. Camus, The Rebel, p. 56.

25. Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov, p. 291.

26. Adamovich and others, Out of the Fire, p. 330 (ellipses in the original).